Why do we need more women police? A look at India, Liberia, and Ukraine provides evidence.

If the protection of women and girls is a pillar of the Women, Peace and Security (WPS) movement, then we need female police officers to hold that pillar up. There are two key reasons for this. First, women exhibit stronger skills in de-escalation. Statistically, female officers are less likely to become aggressive during a confrontation or to fire their weapons while on duty. Their presence in communities builds trust between the local populations and police forces and diminishes instances of deadly force. The second reason is that women are also more likely to report sexual assault or gender-based violence to other women. This means that incorporating women into local police guarantees a higher rate of reporting of sexual and gender-based violence (SGBV) and better protection for women and girls.

The success of this approach has been tested in a variety of environments, and the results unanimously show that incorporating women has clear benefits. Regardless of state fragility, economics, or culture, integrating more women in local police allows for better protection—and for more trust.

India

In India, a simple solution was utilized to address everyday harassment commonly known as “Eve-teasing.” In a country where four out of five women report experiencing public sexual harassment, local officials responded with all-female teams. These units are trained in martial arts, patrol in pairs, and have one specific purpose: to identify and stop harassment. Launched in May of 2017, this initiative began in Jaipur and soon spread to its neighboring city, Udaipur.

Previously, police had developed “anti-Romeo” squads for essentially the same purpose, but these units were male-dominated and developed a bad reputation for targeting romantic couples instead of legitimate harassment. Female police officers are better able to identify harassment and appear more approachable to other women.

Jaipur has sixty police stations, of which only four are dedicated to women’s issues, creating a shortage when women want to lodge complaints. The city is looking to improve this, but it is not the only step needed to prevent sexual harassment. Cultural attitudes need to be changed, which will involve more extensive gender training for male and female police officers alike.

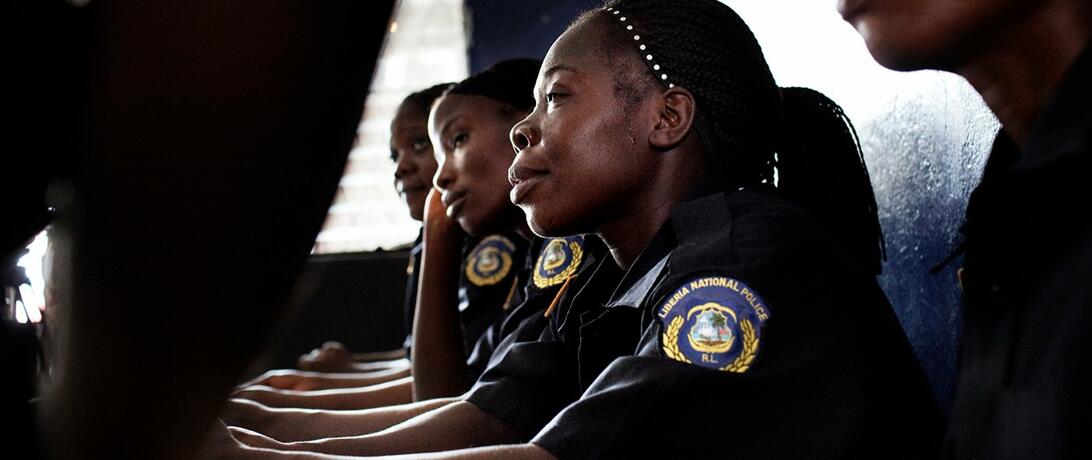

Liberia

In Liberia, fourteen years of civil war left the country in a fragile state with the death of approximately 3 million civilians and the displacement of hundreds of thousands. Security was the government’s top concern, but violence—and particularly SGBV—continued to be a challenge. The Liberian National Police (LNP) had been perpetrators of rape and murder during the war, and it was critical for Liberia to rebuild the reputation of the force to gain back the confidence of its citizens.

One group that had already built such rapport was women. Liberian women had conducted the country’s interfaith peace movement leading to the democratic election of Ellen Johnson Sirleaf as the country’s first female president. Liberia capitalized on the positive reputation of women by incorporating them into the police force and establishing the Women and Children’s Protection Section (WACPS). The goal was to increase the percentage of female officers to 20 percent by 2014 and to improve the LNP’s responsiveness to SGBV.

Prior to 2005, most Liberians did not consider rape a crime, did not know how to preserve evidence for police, and did not know where to go for help with reporting. WACPS worked to change the cultural standards that reinforced SGBV as normal. Rape became the highest reported crime in Liberia as the local population began to view it as a crime and to gain faith in the LNP as a source of protection. While there were still obstacles to reporting—and many women still failed to report or had trouble navigating local courts—the integration of women and targeted awareness-raising of SGBV had an overall positive result.

Ukraine

Several factors contribute to SGBV in Ukraine, a country that has seen rising cases due to the dismissal of police, returned soldiers, and vulnerability due to conflict. Approximately 1.7 million people from eastern Ukraine and Crimea have been displaced within the country.

As in the other cases, belief in the local police force is a key factor in reporting SGBV in Ukraine, and Ukrainian female police officers are viewed as more trustworthy than men. In a survey conducted by IREX, 32 percent of respondents felt that female officers were more approachable than males, and only 5 percent of respondents felt that male police were more approachable than women, with similar results for perceptions of corruption. A critical 16 percent of women were more willing to go to female police officers for assistance.

In Kiev, approximately half of the phone calls to police come from women who have experienced domestic violence. This highlights a very real need for adequate protection. Ukraine has taken several measures on this front, including the adoption of a National Action Plan on United Nations Security Council Resolution 1325 on WPS and the training of police on proper SGBV response. However, many women remain vulnerable due to ongoing conflict, highlighting the need for continued efforts. Increasing the number of women in Ukraine’s police force would go a long way toward improving trust and response to SGBV cases.

Why More Women?

The data are clear that integrating more women into local police forces increases trust, reporting of SGBV, and especially the protection of women and girls from SGBV. That being said, women are still underrepresented on police forces globally, and their impact needs to be backed by state laws and court systems that support women and girls when they come forward. Incorporating more women into the police force is a good first step, but there continues to be a need for structural support for survivors of SGVB for the concept to be truly effective.

Article Details

Published

Topic

Program

Content Type

Opinion & Insights