A transformative approach to gender mainstreaming, in which data is collected, analyzed, and used in a way that fits the new social structures can better help the displaced population rebuild their lives.

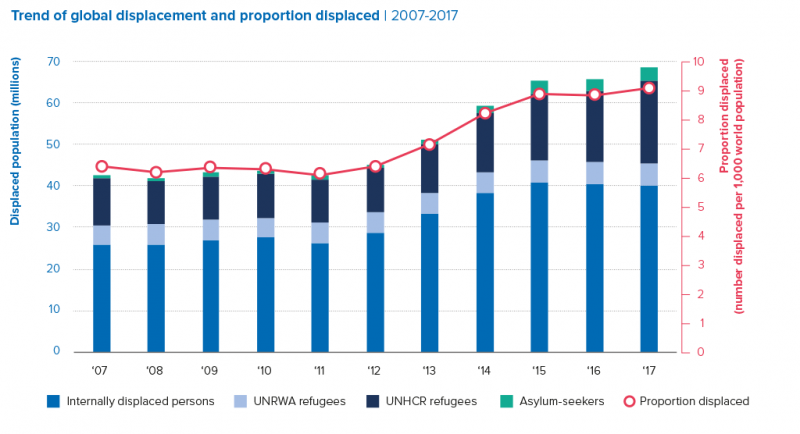

World Refugee Day has come and gone, but the need for transformative gender mainstreaming within refugee policies remains. Currently, there are 68.5 million[1] people across the globe who have been uprooted from their homes due to conflict or persecution. People’s lives and their social fabrics have been left in tatters and new unfamiliar living environments affect the social roles and responsibilities of both men and women. Their former support structures have broken down and stress is at a high.

The United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), the largest agency focused on these matters, has acknowledged that displacement has different consequences for women and girls than for men and boys. However, there is still room to improve gender mainstreaming in the camps. Studies have found that despite gender being a policy priority, implementation continues to be “slow and ad hoc.”[2]

The integrative approach to mainstreaming that UNHCR is currently implementing lacks the ability to fundamentally shift understandings or representations of refugees and asylum seekers. It has not moved away from a discourse in which women are viewed as victims. Gender mainstreaming within camps needs to be able to transform international norms and introduce new understandings. Approaching gender mainstreaming in this way is crucial to moving forward as conflicts become deadlier, protracted, and more frequent.

The figure above shows the number of displaced populations from 2007-2014. Photo Courtesy of the International Organization for Migration.

For a long time, any consideration of gender issues was absent form discourse and debate on refugees and asylum. The 1951 Refugee Convention and the 1967 Protocol Relating to Refugees remain the major international convention regulating the protection of refugees. The 1951 convention was negotiated primarily by the United States and its European allies, the treaty was highly limited in its application, did not mention gender and was mostly aimed at dealing with cases of people arriving in the west from one of the Soviet bloc countries. Thus, as perceived by the convention, a refugee was an individual persecuted by a totalitarian regime because of his or her political views or activism. Large groups of displaced people fleeing from international conflicts or civil wars were not envisaged as refugees in the beginning.

Gender-aware approaches within refugee policies began to enter the international consciousness and gained support in the lead up to the World Conference on Women, held in Nairobi in 1985. At the same time, it became more and more difficult to ignore women refugees, particularly when large numbers of them were living in camps. One of the first signs of gendered issues in a refugee crisis came during the massive forced migrations in southeast Asia in the 1980s. Reports of sexual assaults by pirates against fleeing refugees, who became known as the ‘boat people,’ were broadcast globally.[2]

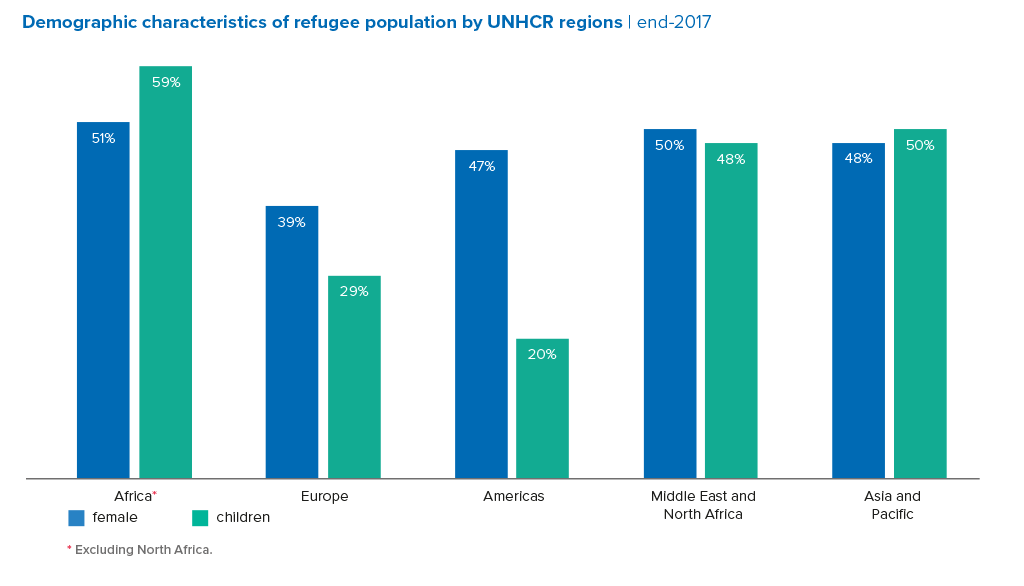

Demographics of displaced populations across UNHCR regions. Photo courtesy of UNHCR.

In 1991, UNHCR drafted the Guidelines for the Protection of Refugee Women. While these guidelines were eventually replaced by the UNCHR Handbook for the Protection of Women and Girls, an assessment done in 2001 by the Women’s Commission for Refugee Women and Children showed that the overall implementation was “uneven and incomplete, occurring on an ad hoc basis in certain sites rather than a globally consistent and systematic way.” [3]

Several more United Nations Security Council resolutions came after these guidelines that either mentioned gender or made way for the requirement of gender advisors to be deployed. None have successfully addressed all the issues women face when displaced.

Thus, although gender mainstreaming is an officially accepted target for UNHCR and its partner organizations, there is still a long way to go before it really becomes effective and is transformed in practice into equal protection for men and women asylum seekers and refugees.

The mixed results of UNHCR’s attempts to integrate gender mainstreaming into its policies and programs can be traced back to a variety of causes. These include the structure of the organization and its institutional culture, the policies of donor governments, and their dominant representations, which portray women refugees as helpless victims. These reinforce the difference between ‘us’ and ‘them.’ Relations of power, which start off as highly unequal, view women as a special or separate group, and have further marginalized them. They have ignored the relational aspects of gender that affect both women and men in displaced situations.

Another study, in which UNHCR employees were interviewed, showed that although the organization has officially adopted gender mainstreaming, the belief that international refugee conventions and instruments are non-discriminatory. The study also found that staff believe there is no need for separate actions for men and women. Many of those who were interviewed ignored questions relating to gender equality and women’s rights. They were sometimes reluctant to integrate these questions into their general work, feeling as if they had “more important” priorities. [4]

Other barriers to full implementation include a lack of female UNHR staff; a serious obstacle to obtaining information from refugee women to address the specific issues they face, as well as a lack of accurate data on some refugee populations.

There are ways in which UNHCR can develop transformative initiatives that would help fully implement gender mainstreaming throughout refugee policies and camps. These initiatives should effectively build on the capacity of women affected by armed conflict; support internally displaced women and children, especially as they push for a return to their homes; and encourage women’s participation in all aspects of camp life.

There needs to be a global application of the current international norms. These include the guiding principles on internal displacement, and the use of a rights-based approach based on equality, accountability, participation and protection. Women’s participation should be built into the delivery of services within the camp.

In addition, the Inter-Agency Standing Committee Policy Statement on the Integration of a Gender Perspective in Humanitarian Assistance needs to be fully implemented across the board. This would ensure that gender issues are better brought into humanitarian assistance activities and would also pay the way for measure to promote the positive role women can play in post-conflict peacebuilding, reconstruction, and reconciliation.

Consideration of the local and international contexts should be at the forefront when implementing gender throughout all programs. Having more informed understanding and analysis of the social structures of displaced populations that determine the relations, behavior, coping mechanisms, and capacity for adjustment will better inform policies. By mobilizing displaced populations through social structures to change attitudes can be used to facilitate a systematic consultative process with women in the day-to-day management in camp committees. [5]

If the interests and participation of women refugees are to be guaranteed, then the voices of these women need to be heard. A transformative approach to gender mainstreaming, in which data is collected, analyzed, and used in a way that fits the new social structures, can better help the displaced population rebuild their lives.

[1] n.d. UNHCR. Accessed 06 21, 2018. http://www.unhcr.org/en-us/.

[2] Gururaja, Srilakshmi. n.d. Gender dimensions of displacement. Forced Migration.

[3] ibid

[4] ibid

[5] Gururaja, Srilakshmi. n.d. Gender dimensions of displacement. Forced Migration.

[6] Gururaja, Srilakshmi. n.d. Gender dimensions of displacement. Forced Migration.

Article Details

Published

Written by

Topic

Program

Content Type

Opinion & Insights