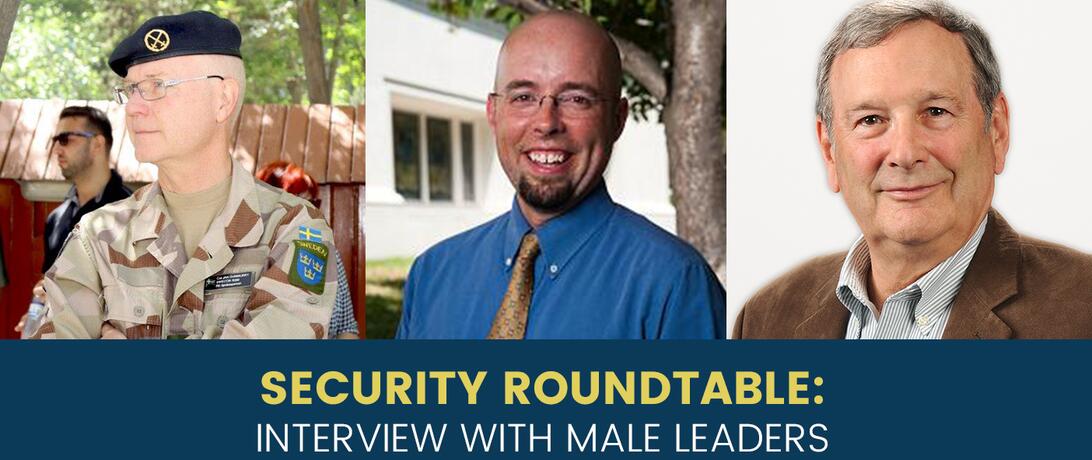

Three male leaders in the field of Women, Peace and Security share their experiences paving the way in engaging men in women's rights.

The topic of Women, Peace, and Security and UNSCR 1325 has become recognized as a key issue in global discussions today. While the focus of UNSCR 1325 is on empowering women, men—and especially male leaders—are needed to advance the agenda forward successfully. One of the most important shifts in international norms has been the public and vocal involvement of men in promoting women’s equality. Men’s movements that promote women’s rights hold significant potential to breakthrough old norms and social biases that prevent women from fully participating in international peace and security decision-making. It is now clear that creating partnerships with men is critical to establishing gender equality and ending gender based violence globally.

The following interview is the first in our Security Roundtable series. It illustrates the work of three men who are paving the way for other men to get engaged in advancing women’s rights, particularly in the field of international security

Ambassador Steve Steiner (Ret.) is the Gender Advisor to the Center for Gender and Peacebuilding at the United States Institute for Peace. He has previously served in the Department of State’s Office of Global Women’s Issues and the Office to Monitor and Combat Trafficking in Persons. Steiner served for 36 years in the United States Foreign Service and completed tours of duty at the Embassy in Moscow and the State Department’s Offices of the Soviet Union and West German Affairs. He served from 1983 to 1988 as Director of Defense Programs on the US National Security Council Staff.

Commander Jan Dunmurray served as the Commanding Officer at the Nordic Center for Gender in Military Operations at the Swedish Armed Forces International Center—SWEDINT. He has served as Chief of Operations at the UN Mission in Macedonia, and has leadership positions in NATO-led operations in KOSOVO and Afghanistan. He is decorated with many honors for his service to the Swedish Armed Forces, NATO/ISAF, and UN missions. He is currently deployed on mission in Afghanistan.

Joseph Vess formerly served as a Senior Program Officer at Promundo, focusing on sexual and gender-based violence prevention and men's engagement in crisis, conflict and post-conflict settings. The projects he contributed to included development and implementation of the Living Peace program in the Democratic Republic of Congo, Burundi and Sierra Leone and he also supported violence prevention and youth development interventions with young men in Lebanon and the former Yugoslavia. He has a master's in International Peace and Conflict Resolution from American University, where he focused on sexual violence in armed conflict in the Great Lakes region of Africa. He is currently at Emory & Henry College, where he works with students, faculty, and staff to incorporate project-based learning into every aspect of the Emory & Henry educational experience. He also facilitates gender-equitable fatherhood groups at the Southwest Virginia Regional Jail Authority facility in Abingdon, Virginia.

Sahana Dharmapuri (SD): Thanks for joining me. In the last several years there’s been a dramatic increase in the visibility of men working on gender equality and ending violence against women. We’ve seen groups like the White Ribbon Campaign march against rape in India and South Africa. But why should men get involved with the Women, Peace and Security agenda, as set out by the Security Council in UNSCR 1325?

Joe Vess (JV): I think it is vital for men to be engaged to better understand, support and—where appropriate—be active participants in advancing the Women, Peace and Security (WPS) agenda. There are already plenty of men who are actively working against women’s equality and equal role in peace-building, so I believe it’s vital that other men be engaged to support it. There are countless men who are sympathetic or even supportive of the WPS agenda’s goals who have simply not been engaged to participate, so bringing them along as allies only strengthens the movement.

Ambassador Steve Steiner (Ret.) (SS): I think it’s obvious that men should engage with this agenda and women’s rights. If you want a solid democracy, you have to empower fifty percent of the population. Men and women have to work together. You won’t get to women’s rights unless there are enough men on board—good men. One aspect of that is showing men that women’s equality and advancement is not a zero sum game. Sometimes you have to show that inviting women to a capacity-building program is good for the men, too. It’s good for their families, and their community.

CMDR Jan Dunmurray (JD): Definitely. If men don’t get involved there will be no change of the security situation for women and girls, not only in conflicts but in broader contexts.

SD: Women have been working on this agenda for a long time, even before the Beijing Platform. What can men add to the work that’s been done already? What are men’s unique contributions?

SS: Not sure I’d use the word unique. Men have an indispensable contribution to make because there won’t be any equality without them. Men have to accept the equal standing of women and equal opportunity for women. Sometimes it’s easier with men who have a daughter in college because suddenly they feel the inequalities in a more personal way—it impacts them. And that’s helpful. It’s an opportunity. If we can get that new insight and changed attitude to spread across society, we’re doing ok.

JV: I think that the role that men can play really depends on the context and needs of a particular situation, and should really be decided in consultation and partnership with women-led groups. I think men who are aware and knowledgeable about this issue and committed to gender equality and the WPS agenda have an obligation to role model equitable male participation in this area to other men. There are very few men in fragile and post-conflict settings, or men in positions of power, who are doing this, making it even more imperative for those who have influence to use it appropriately. In other settings, I think men need to add to women’s efforts to hold political and economic leaders accountable for their gender inequitable actions before, during, and after conflict.

JD: I agree. Traditionally, more men have held leadership positions. Since they are in leadership positions, men have an opportunity and the responsibility to use that position of power to advance women.

Today, it’s a still a male dominated world and a lot of men are leaders. Sometimes, in order to move a controversial agenda forward it takes a man to talk to a man. This is a bad expression, but sometimes that can be the case. This is because male leaders will listen to other male leaders. In some cases it’s because of the mutual respect for each other’s positions. In the best world, this shouldn’t be the case, but there are still some conservative men who are more open to listening to a man than to a woman.

SD: Can you give an example from your own experience of why you think it’s important that men promote equality between the sexes?

SS: I get asked this a lot. People ask me, “How can you switch from nuclear arms negotiations to women’s empowerment issues?”

I say, it’s simple. Our team was working on US-Soviet negotiations. I was working on the START Treaty. I led the US side in the implementation of START Treaty and Intermediate Range Nuclear Forces (INF) Treaty. We felt that the work of reducing the arsenals of nuclear arms (by the destruction of missiles and launchers) under the conditions of on-site inspections was helping to create a safer world. When I retired from the Foreign Service, I began a second career on democracy and human rights work. This led me directly to work on women’s rights. I saw immediately that there is no democracy without women’s rights and that women’s rights makes a safer and more decent world.

Another example is—we’ve found it a challenge to get men engaged on women’s rights. I’ve found that when you advertise forums on women’s rights or gender you won’t get a lot of men showing up. But when we (USIP) did our first forum on this issue last fall, we called it, Men, Peace & Security: Men As Agents of Change. And we got over 200 participants, 55% of them were men, including some amazing men from the Global South. You have to show men that equal rights for women is their issue, too. It’s not just about women. It’s about creating a better country, improving wellbeing and security for everyone.

Maybe the word security helps to get men in the room, too. You can’t have the dialogue without getting the men to the table. The message has to be, “Be part of the security agenda, and the security agenda naturally has to address gender.”

SD: Have you had to deal with resistance to including men in this predominantly “women’s” agenda—by that I mean, it’s an agenda created and led by women. Have you had to deal with push back?

JD: Yes, in the context of my work with military operations. In the beginning, when I started working with gender perspective, it wasn’t perceived as very important by my male peers. Male colleagues questioned my choice of topic and interest. I heard comments like, “why do you have to work on gender?” meaning they viewed it as less important and not a real military task. But now things have changed dramatically. I would say that today most military personnel in the Swedish Armed Forces are interested and want to learn more. And I’ve seen this trend internationally, too. I think it’s because the issue of women in war and peace has been on the political agenda a long time, and more people have heard about the issues now. And when foreign military officers (male and female) come to the Nordic Center for Gender in Military Operations, they can get real experience. Our courses normally have participants from 14-18 Nations, equal percentage of women and men, exchanging experiences and learn a lot from each other. It’s great to meet with male military officers from traditionally conservative societies who are excited to work on gender. It’s very important to the success of future military operations to create stability in conflict zones.

JV: One area we [at Promundo] have seen resistance to support for gender equality and women’s empowerment is in the Eastern DRC. However, deeper research with men in this region found that much of their violence and gender-inequitable behavior was being driven by trauma and a sense of disempowerment resulting from the decades of conflict, poverty and displacement. This is not to excuse the violence, but was rather to help Promundo design an intervention that accurately addressed the root causes and drivers of men’s behavior in this context. After developing a 15-session curriculum based on principles of group therapy and group education, the results we found included improved partner relations and reconciliation between partners; improved economic outcomes and increased trust between partners; and improved gender relations and sexual relationships. One of the next challenges then is how we ensure these household-level improvements translate to larger, community- and society-wide gender equality.

SS: I experienced some backlash when I was at the State Department, working with Ambassador Melanne Verveer. I would go out to the Foreign Service Institute to train classes of US military and civilians going overseas to Iraq and Afghanistan to serve, for example on Provincial Reconstruction Teams to engage with the local communities.

Invariably, I’d get one or two people in each class who challenged me and said, “What right do we have to tell them how to treat their women, or to judge their religion?”

I pushed back. My answer was and still is this. First, it is US foreign policy to promote the equal rights of women, and you work for the US government. Second, it is in line with international covenants such as the Universal Declaration of Human rights, to which we are a party. Third, I’ve talked with a lot of women from Muslim countries who say that their religion is being deliberately misused and misinterpreted to prevent the advancement of women. It is often tribal practices that are influencing the interpretation of religion. There were will always be one or two saying “how dare we do this.” I’ve learned that I have to expect that there will be push back.

SD: What’s your advice to other men and women facing the challenges of promoting women’s equality in peace-building and international security?

SS: I’ll start with advice to women first. Usually women who work on this issue focus on engaging other women. They are good at networking, and they are good at bringing more women to the table. But some of them are not very good at engaging men. I’ll say, “You’ve got to engage the men, too, on this issue, otherwise you won’t be successful moving forward.”

Advice I would give to men is this: You won’t have a good or powerful or successful country without women, and without supporting the equality of women. This is not a zero-sum game. Women’s equality benefits everyone. Women entrepreneurs enhance your economy. In a lot of countries men want their daughters to be educated. If your wife is educated, you’ll get more educated sons and daughters. It’s time to include women in the workforce and bring their talents to bear on the economy.

JD: Advice? Well, first, I would say it’s the correct thing to do to promote not only women’s rights, but all people’s equal rights, especially in matters of international peace and security. If we don’t involve women at all levels, we’ll fail at creating a sustainable peace. And last, I think that using gender perspective and including women in international peace and security is the smart thing to do. A question I would like to put to young men is this, “Don’t you want to be smart?”

JV: While I think it still seems very much an uphill battle, the reality is that women have already accomplished a tremendous, staggering amount in changing the terms of discourse and making the WPS agenda not a dream, but a reality that is advancing. I think we need to keep looking to the visionary thinkers in the field who have accomplished so much to figure out how to move forward effectively. At the same time, I think it is important to engage the next generation of young men and women around these issues. Regarding men specifically, Promundo’s research has shown that the younger generation of men in many countries is more supportive of gender equality than older generations. I think it can be very valuable to pro-actively engage these young men, solicit their ideas and provide opportunities for them to get involved in promoting women’s equality in peace and security. There are many people around the world who would gladly harness these young men’s energy for violent ends, it’s a great opportunity for the WPS field to show young men that there are ways they can contribute to a better world that are positive and hopeful, rather than dark and destructive.

Article Details

Published

Topic

Program

Content Type

Opinion & Insights