OSF is excited to be publishing our Annotated Bibliography on Women, Peace and Security (out soon)! Read more here for evidence as to why this movement really works!

There are two main approaches to Women, Peace and Security (WPS). The first is simple. It is the “human rights argument,” which is essentially that, as women make up one-half of the global population, they ought to have one-half of the say in global decision-making. The other is more complex. It is the “effectiveness argument” of WPS, that women not only have a natural right to sit at the table but they also improve the outcomes and impact of major decision-making processes. The first is easy to prove, but the second requires some research.

As a result, our team has spent the last two years compiling our upcoming annotated bibliography, which focuses on answering the research question, “How does implementing the Women, Peace and Security agenda make international peace and security efforts more effective?”

This highly selective bibliography veers away from a long-held focus on women’s rights and protection with an eye instead toward providing evidence that women are effective agents of change. It deviates from the human rights argument that women need to be included because they are half of the global population and instead focuses almost entirely on the effectiveness argument for Women, Peace and Security by showing that this agenda improves conditions for women, men, boys, and girls alike.

In light of the bibliography’s upcoming publication, here are the highlights from the project’s four major sections of political participation, peacebuilding and conflict resolution, peace and security operations, and countering violent extremism (CVE) and counterterrorism.

Political Participation

One of the first things the research revealed was that having more women in politics impacts the effectiveness and policy of governments.

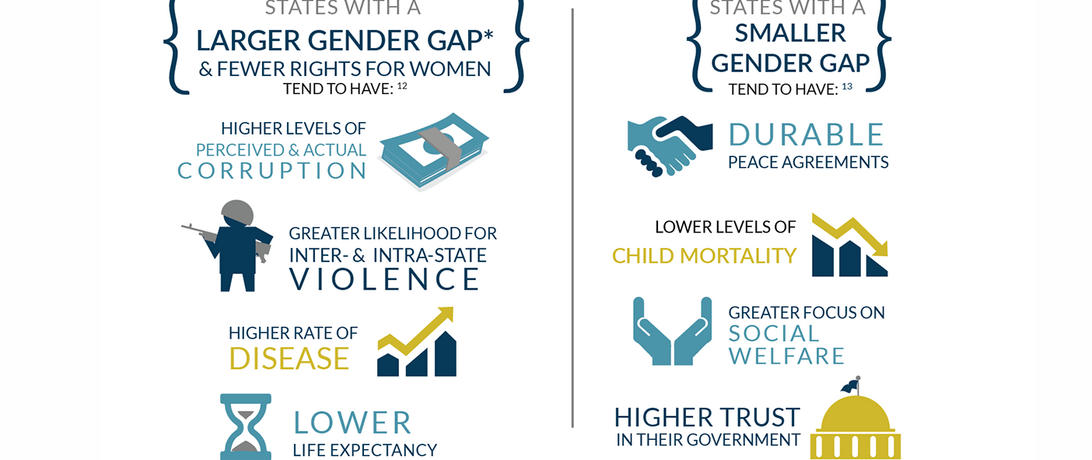

The findings indicate that women are more effective legislators. A study of the US Congress found that women in the minority party were 31 percent more effective at pushing legislation through than their male counterparts, and women in the majority were 5 percent more effective. Another study that investigated whether women were really the “fairer sex” found a correlation between the proportion of women in a given country’s legislature and the level of perceived corruption in that state. Other studies found a direct correlation between greater gender equality in politics and diminished levels of actual corruption—although these findings seemed to be limited to functional democracies where the removal of corrupt candidates from office was a viable option. Furthermore, greater political gender equality, measured by the presence of both women chief executives and women in parliament, correlated with lower levels of human rights abuses at the hands of state agents.

When it comes to policy, female parliamentarians are 122 percent more likely than their male counterparts to engage in a health-care debate.

While state aggression tends to increase when a female leader is the head of state during times of warfare, one study found that a 5 percent increase in women in a state legislature decreases the state’s overall likelihood to use violence by nearly five times. When at least 35 percent of the legislature was female, it reduced the likelihood of a state relapsing into civil war to virtually zero.

Peacebuilding and Conflict Resolution

In peacebuilding, studies showed that women and men not only had different wartime experiences but also created different outcomes when they were part of the process. This is important because including women in peace processes makes them 64 percent less likely to fail and 35 percent more likely to last at least fifteen years, meaning women’s participation leads to more sustainable peace. This was evident in country case studies such as Northern Ireland, South Africa, and Guatemala where national women’s movements were critical to peacemaking.

A study of thirty-nine peace agreements found that the thirty-one that had failed had all also failed to include women. On the flip side, another project looked at forty peace processes over the course of thirty-five years and found that, when women were able to influence peace processes, an agreement was almost always reached. In fact, there have been no historical instances in which women’s participation was shown to have a negative impact on the process.

Peace and Security Operations

When it came to women in peace and security operations, integrating more women has several outcomes that are good for women as well as for whole communities.

As peacekeepers, women foster greater community trust and are viewed as more accessible to other women, who are more likely to come forward to report instances of sexual and gender-based violence to a woman peacekeeper than to a man. In the Democratic Republic of Congo, this led to UN mission success when a gender advisor requested an audience with only the women of a community that was experiencing rebel attacks. When the women sat down alone, they felt comfortable enough to speak up about the sexual violence they had been experiencing at the hands of rebel groups and to identify where the rebels had been hiding on the outskirts of the fields where the women worked. This information led to new patrols that not only helped to protect women but also decreased the number of attacks on the village at night, a clear improvement for the whole community.

Statistical evidence shows that the mere presence of peacekeeping missions can have a positive impact on state likelihood of adopting gender balance reforms. States without peacekeeping missions had only a 51 percent probability of adopting reforms, whereas those with peacekeeping missions had a 73 percent probability of adopting them. In other studies, it was implied that this relationship was reversed and that countries with better preexisting gender equality were more likely to have successful peacekeeping operations, so there is a clear relationship here.

Among peacekeeping forces, the UN Department of Peacekeeping Operations found that having a critical mass of women peacekeepers of 30 percent or higher had a civilizing effect on peacekeeping forces and helped to mitigate instances of sexual and gender-based violence perpetrated by members of peacekeeping troops.

Countering Violent Extremism and Counterterrorism

In the field of CVE, the research is limited, but the research that does exist strongly suggests that women, and especially mothers, have substantial roles to play in countering violent extremism.

Women’s added value is evident in initiatives such as the Daughters of Iraq, where hiring Iraqi women to work at checkpoints and conduct searches of other women helped to mitigate the short-term threat of terrorist attacks. Another programming initiative instituted so-called Mother’s Schools to train women in how to detect radicalization among their children and provide counternarratives in the home. This was shown to have a mitigating effect by lessening their children’s likelihood of joining terrorist or violent extremist groups.

This body of work needs further exploration. Specifically, we need to know more about why women radicalize and join violent extremist groups and how to monitor and evaluate the effectiveness of programs that teach women to combat violent extremism from the home and through their family networks.

Key Takeaways

Based on this body of literature, we have developed several recommendations for policymakers to advance the WPS agenda. The following four provide a summary of our key points:

- Increase the participation of women in each of these sectors through “supply side” solutions such as electoral finance assistance, training, and capacity-building so that women can engage effectively.

- Recognize and scale up women’s local peacebuilding efforts—and use them as a model for larger-scale efforts.

- Fund recruitment of more women into peacekeeping and security forces and build teams to work at the local level.

- Work to understand how women can be integrated into CVE and counterterrorism efforts, and build their capacity to do so.

The data in this bibliography show that women’s participation leads to improved governance, peacebuilding, peace and security operations, and CVE efforts. Keep an eye on the website as it will be out soon!

Article Details

Published

Topic

Program

Content Type

Opinion & Insights