While civil society engagement is critical to the success of the Women, Peace and Security agenda, Catie Fowler argues that funding is also vital to implementation.

This is the third installment in a blog series on civil society engagement with the Women, Peace and Security agenda. The series shares perspectives from multiple focus areas of One Earth Future. Lead advisors for the series include Alexandra Amling, Kelsey Coolidge, and Catie Fowler. Read the first two blogs here and here.

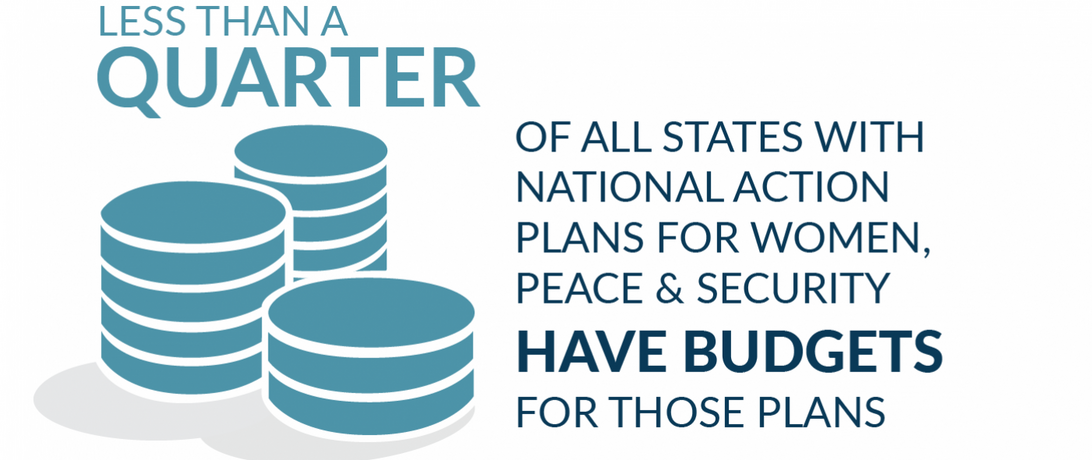

As of 2018, 76 countries have made state commitments to national action plans (NAPs) for Women, Peace and Security (WPS). However, only 22 percent of those plans have included allocated budgets. A plan without funding is like a bus without a motor: it may have a willing driver and passengers, but it will never reach its destination.

Multiple studies point to lack of funding as a real obstacle to the successful implementation of the WPS agenda. In 2011, Cordaid, the Global Network of Women Peacebuilders, and the International Civil Society Action Network released the report, “Costing and Financing 1325: Examining the Resources Needed to Implement UN Security Council Resolution 1325 at the National Level as Well as the Gains, Gaps and Glitches on Financing the Women, Peace and Security Agenda.” Although an older report, the recommendations it made remain relevant to the field of WPS today:

- Encourage and support local ownership of national action plans and alternative mechanisms for implementation of SCR 1325.

- Establish a transparent and inclusive financial management platform for 1325 implementation composed of donors, governments, civil society, private sector, and multilateral organizations, including the UN.

- Improve coordination and promote collaboration among different actors involved in women and peace and security advocacy and programming.

- Conduct a comprehensive and accurate assessment of needs, resources, and capacities; plan and mobilize resources accordingly.

- Explore partnerships with the private sector.

- Earmark 1325 funds, review military and other government budgets, and identify windows upon which 1325 implementation could be funded.

- Recognize and enhance civil society’s capacity to generate and manage financial resources dedicated to 1325 implementation.

- Allocate adequate resources for independent monitoring and evaluation of 1325 implementation and other women and peace and security initiatives.

Similarly, in a 2014 review of 27 countries by the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE), the two primary reasons discovered for the slow progress of the WPS agenda were lack of capacity and scarce resources’ being earmarked for the agenda. Again in 2016, an investigation of the implementation of four country NAPs by One Earth Future Research and Inclusive Security recommended that countries “establish accurate cost estimates, and identify and allocate sufficient funding in the NAP’s development phase.”

A brief comparison of NAP financing in two countries, the Democratic Republic of Congo and Canada, provides a clear indication that funding played a large role in the relative success of each state’s plan.

Examples from the Democratic Republic of Congo, Canada, the Philippines, and Sweden

In the Democratic Republic of Congo, lack of funding was an obstacle to implementation, despite an active civil society network for WPS. The budget for the plan was estimated at $59 million, but members of civil society quickly noticed that there was no money allocated to it. When donors contributed funds toward the implementation of the NAP, they were frequently diverted to other gender-related efforts that were not specific to WPS and were difficult for civil society to access.

Dedicated funding for NAPs remains relatively rare but also helps to facilitate implementation. An example of a state that did incorporate a funded budget in its plan is Canada. The government of Canada also announced $150 million in funding for women’s civil society organizations as part of its feminist foreign policy. The Canadian NAP states this is because local women’s organizations are aware, properly skilled, and well-placed to advance the WPS agenda in areas including peace negotiations, conflict prevention, humanitarian action, and peacebuilding.

The majority of states with NAPs are more developed and have more state resources available for implementation, but that is not to say that developing countries lack the capacity to fund their own plans. For example, the Philippines was both the first country in Asia to draft its own NAP and the first developing country to fund it using entirely its own money.

Regardless of a state’s capacity to fund its own plans, it is important that states that lack funding still include a budget to guarantee they are successful. In the case of the Philippines, this was done through gender responsive budgeting, breaking down the national budget to determine its impact on women and men. By undergoing this type of analysis, states that have limited funds may find ways to reallocate funds to the WPS agenda. For states that have more externally or donor-focused NAPs, the funding for implementation of their national plans might come out of other budgets, such as preexisting military or development funds, but may not always have a budget that is tied to the NAP. In countries such as Sweden and Canada, which have integrated gender equality into their goals with feminist foreign policies, funding for WPS may come from other sources within their respective governments.

Funding through Partnerships

If a state is incapable of funding its own NAP, financing can be attained through donor countries or civil society organizations (CSOs).

Perhaps the most prominent method of WPS financing for developing countries is to cooperate with donor states. The top funders of gender equality and women’s empowerment in developing states are developed countries and institutions of the European Union. When it comes to WPS initiatives specifically, donor countries can offer expertise in addition to funding.

A technique called “twinning” between donor and recipient states has been successful for drafting NAPs. This process, recommended by the Civil Society Advisory Group on Women, Peace and Security on the 10th anniversary of UNSCR 1325, is defined as when a “country will commit to twinning with [another] country in providing financial and technical support for a period of five years in developing and implementing a national action plan for implementing UNSCR 1325.” This new tool for diplomacy and development is a result of the collaborative nature of the WPS movement. Notably, the process of twinning means that beneficiary countries are equally helping to guide the NAP drafting process in donor countries as donor countries are helping to guide the NAP drafting process in beneficiary countries. Twinning has been utilized in a variety of contexts, including in cooperation between Liberia, East Timor, and Ireland, as well as between Kenya and Finland.

Ideally, states drafting and implementing their own NAPs for WPS would also have the state capacity to fund their implementation, and there are a variety of ways for them to do so. However, when local funding is not available for implementation, alternatives are certainly accessible. Another way to fund WPS implementation is for international non-governmental organizations (INGOs) in the global North to align with CSOs in the global South. These organizations are better financed to provide necessary funds than local women’s organizations, and they can help to amplify women’s voices on the ground by providing them funding assistance. For example, CARE has been directly engaged in the implementation of UNSCR 1325 in countries such as Afghanistan, Uganda, and Nepal, an effort the organization centers around grassroots engagement.

In lieu of dedicating their own funding for NAPs, developing countries can and should reach out to donor countries or INGOs to ensure their goals for implementation are achievable.

To learn more about which countries have national action plans for Women, Peace and Security, check out our National Action Plan Map!

This blog was originally published on August 24, 2018 and updated to reflect the most current information on September 14, 2018.

Article Details

Published

Topic

Program

Content Type

Opinion & Insights